The Man in the High Castle season 2, your next online TV addiction after The Crown, premieres this month on Amazon Prime. Based on Philip K. Dick’s seminal work of alternative history fiction, the show imagines a nightmare ‘60s America under occupation and divided between the victorious Axis powers of Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan. The premise of a hypothetical Axis victory has captivated historians, science fiction writers and, regrettably, the occasional white-supremacist fanboy for decades. Now, art history people want in on the masochistic fun.

What would the art world look like if Hitler had won the war? Actually, as a failed painter and art enthusiast (albeit with an amateurish eye and bourgeois taste), the Fuhrer left a meticulously detailed record of just how he envisioned the post-war visual culture of a victorious Reich.

Inside the “Nazi Louvre”

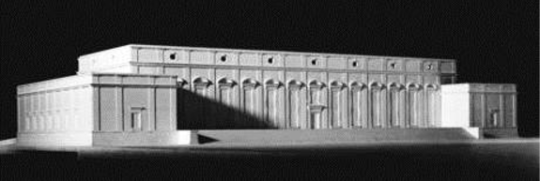

Architectural model of the unrealized Fuhrermuseum.

Hitler’s greatest cultural ambition was to establish the “Fuhrermuseum,” a monumental super-museum in his hometown of Linz, Austria. The museum would have been the centerpiece of a glistening, futurist metropolis on the Danube, dwarfing the nearby cultural capitals of Vienna and Budapest. It would have housed a massive collection of artistic treasures stolen, looted, confiscated and otherwise plundered from countries and peoples under occupation, including Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Here’s a look at a few of Hitler’s favorites, slated for prime wall space in the museum that (thank God) never was.

The Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck, in Saint Bavo Cathedral.

Called the most stolen work of art of all time, the Ghent Altarpiece has been stolen at least 7 times, including by the German Army during World War I, and again by the Nazis during World War II. The head of the Art Protection Unit of the German Army was fired because he opposed the illegal seizure of the altarpiece.

Madonna of Bruges by Michelangelo, in the Church of Our Lady.

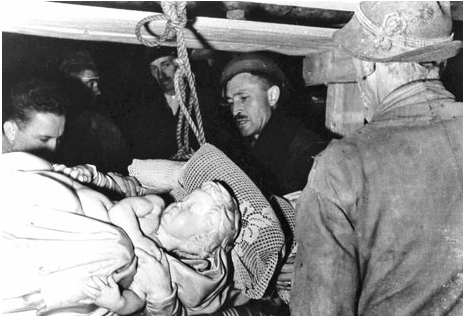

The Madonna of Bruges was stolen from Belgium by Napoleon in 1815, and later wrapped in mattresses by invading Nazis and smuggled into Germany in the back of a Red Cross truck for the planned Fuhrermuseum.

The Astronomer by Johannes Vermeer, in the Louvre Museum.

The Astronomer was one of Hitler’s personal picks. He kept a photograph of it in the Reich Chancellery, lusting after the day it would be crown jewel in his pet project. It was stolen from the Jewish Rothschild family during the Nazi invasion of Paris. You can still find a swastika stamp on the back, from when it was branded for appropriation in the Fuhrermuseum.

This photograph of Carinhall, Hermann Goering’s lavish villa filled with stolen art treasures, gives an idea of how the interior of the Fuhrermuseum might have looked.

All three of these pieces, along with 9,000 others, were hidden in the notorious Altaussee salt mines. Hitler’s scorched earth policy demanded the art be blown up with heavy explosives rather than fall into allied hands, but some conscientious underlings decided only to blow up the tunnels leading into the mines to seal them off from the enemy. Luckily, some baddass dudes known as the Monuments Men (as in the George Clooney movie), dug through and recovered the pieces.

The Monuments Men salvage the Madonna of Bruges from the Altaussee salt mines.

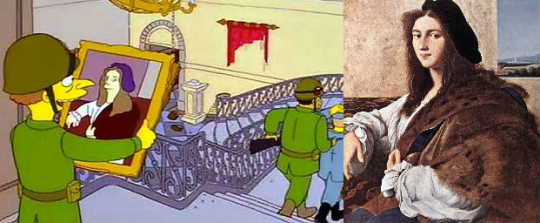

Other works destined for the Fuhrermuseum were not so lucky. Some works were confiscated by the Soviets and others looted by invading American soldiers, never to be seen again. Abe Simpson and Mr. Burns, we’re looking in your direction:

A young Mr. Burns makes off with Portrait of a Young Man by Raphael, one of many Nazi-stolen works, which vanished without a trace during the War.

Venus de Nazi

Rewards of Work by Gisbert Palmie, in the German Historical Museum.

Obviously Hitler had a thing for stolen classical art, but what of contemporary art in the event of a Nazi victory? What modern pieces might have graced the walls of the Fuhrermuseum? Art in a totalitarian regime serves as propaganda to promote the political agenda. In the case of the Third Reich, that basically meant state-sponsored pornography; naked, blue-eyed, blonde-haired babes to “inspire” blue-eyed, blonde-haired dudes to have as many blue-eyed, blonde-haired babies as possible.

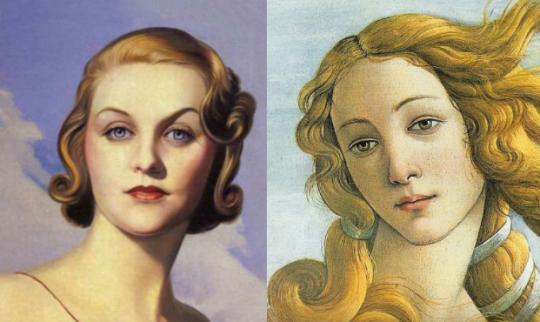

A bevvy of “Aryan” beauties were recruited to model the image of Nazi womanhood. Hitler’s own mistress Eva Braun is rumored to have posed for nudes. British Nazi fangirl Diana Mitford, Lady Mosley, would have been another likely Nazi model had history turned out differently. Hitler was best man at her secret wedding to British fascist leader Oswald Mosley, and an acquaintance described her as “the nearest thing to Botticelli’s Venus that I have ever seen.”

Portrait of Diana Mitford, Lady Mosley (left). Detail of The Birth of Venus in the Uffizi Gallery (right). If the Nazis had won the War, would the likes of Lady Mosley be the beauty icons of our museum-gift-shop refrigerator magnets instead of Simonetta Vespucci and the Mona Lisa?

Not that Hitler was duly impressed by Botticelli; despite his close alliance with Mussolini, the proposed Fuhrermuseum collection had a noted gap in Italian art. Hitler preferred the contemporary “Aryan Realism” of artists like Adolf Ziegler, nicknamed “Official pubic hair painter to the Reich.” Hitler predicted Ziegler would one day outprice the Renaissance masters. Spoiler alert: he was wrong.

The Four Elements: Fire, Water and Earth, Air by Adolf Ziegler, in the Gallery of Modern Art. Perhaps Hitler’s favorite work of contemporary art, he kept it in his Munich apartment.

Blacklisted

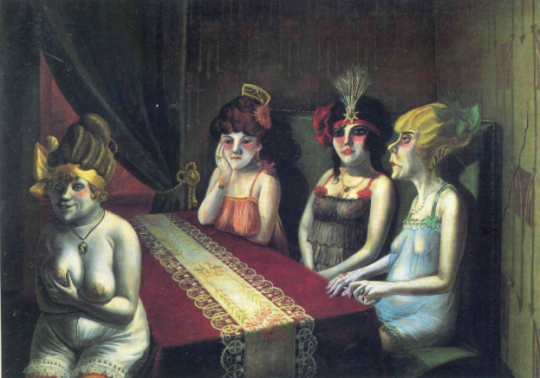

Salon by Otto Dix, in the Stuttgart Art Museum.

Salon seems a fitting follow-up to Ziegler’s The Four Elements. In contrast to the icy, Aryan goddesses of the white-supremacist fantasy, Otto Dix gives us four downtrodden, but infinitely more human Berlin prostitutes. This was just the sort of image of German culture the Nazis hoped to suppress. Hitler tried to get rid of any works by people he saw as genetically inferior or morally depraved, including Jews, intellectuals, political dissenters, alcoholics, drug addicts, homosexuals, the mentally ill…you know, artists.

Hitler decides what’s wrong with the most revolutionary artworks of the 20th Century at the Degenerate Art exhibition, circa 1937.

Dix was prominently featured in the “Degenerate Art Exhibition,” which showcased the very best of modernism and expressionism, or as Hitler saw it, exactly what art should not be. The exhibition was wildly successful, thanks to art lovers and bohemians who flocked to see the forbidden fruit (‘cause if Nazis hate it, it’s gotta be good, right?!). The bulk of the artworks were incinerated after the show, demonstrating just how boring contemporary art would be if Nazis had gotten their hands on the rest of the world’s great masterpieces.

Recreation of a Nazi book-burning, from The Book Thief (2013). “Controversial” art also blazed on the pyres of the Third Reich.

Over 60 million people died as a result of World War II, and the cost to artistic culture is inestimable. All we can do in the aftermath is mourne the art that was lost, thank God for what was saved, shudder at what might have been, and collectively say, “Never again.”

Or, if you are too tantalized by the “what ifs?” of history to look away from the horror that almost came to pass, tune into Amazon Prime for The Man in the High Castle, and log onto Sartle to remember what Hitler did to our artistic heritage.

By: Griff Stecyk