In an awards season which had #oscarssowhite flooding Twitter, and Oprah looking like she was about to punch someone in the face over Selma’s lack of nominations…

…one film that got lost in the shuffle stateside was Belle, an unlikely corsets-and-crinoline epic featuring a black protagonist. Released in 2013, but eligible for the 2014 Academy Awards, this glossy yet unconventional gem received very little buzz in the USA. Some of the only members of the American media to take notice were the African-American Film Critics Association, who honored breakout star Gugu Mbatha-Raw (a British actress of South African descent) as the best actress of the year…this in a year that also featured a portrayal of Coretta Scott King, and a memorable performance by Oscar winner Octavia Spencer. But it is almost an insult to qualify it as a “black” performance. It is a great performance.

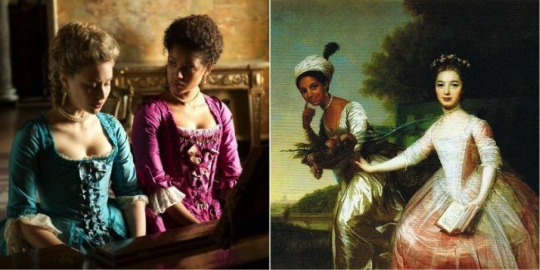

Belle is a Jane Austen-loving art enthusiast’s wet dream: A costume tragicomedy of manners based not on a novel, not on a biography, but on a painting. The genesis of Belle was the eighteenth-century Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Murray, depicting two beautiful girls in fashionable clothes, one black, one white.

Sarah Gadon and Gugu Mbatha-Raw in Belle (left), and the real-life Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray by Johann Zoffany (right).

Screenwriter Misan Sagay (British of Nigerian Descent) was struck by the painting on a tour of Scone Palace as a young student, but the black girl wasn’t even mentioned in the visitor information. Returning several years later, Sagay saw that the mystery girl had been identified as “Dido, the housekeeper’s daughter.” The research that resulted from her curiosity about this elusive figure (a veritable Black Mona Lisa), evolved into a movie by Ghanaian-British director Amma Asante. Sagay and Asante weave threads of the spotty historical record into a plausible narrative, which (if liberal with the facts) is truthful to the spirit of actual events.

Gorgeous newcomer Gugu Mbatha-Raw, in her breakout performance as the title “Belle”.

Gugu Mbatha-Raw is Dido Elizabeth Belle, a biracial heiress who is born the daughter of a slave but raised as a daughter of stately Kenwood House. She struggles to navigate her black identity through the impossibly nuanced class system of Georgian England. Mbatha-Raw delivers that rare thing: a performance that is equal parts raw intuition and eloquently measured emotions.

She is supported by an ensemble of Royal Shakespeare-grade favorites, including Downton Abbey’s Penelope Wilton, two-time Oscar nominees Tom Wilkinson (In The Bedroom, Michael Clayton), and Emily Watson (Breaking the Waves, Hilary and Jackie). Sarah Gadon is appealing and spirited (if suitably washed out) as Dido’s cousin/adoptive sister Elizabeth, who sits beside her in the portrait.

Sarah Gadon as Lady Elizabeth laments the escape of an eligible bachelor.

For two centuries the only known sitter for the portrait was Elizabeth who is now probably the less famous of the two. She was an acquaintance of Jane Austen and some theorize Austen based the character of Fanny Price in Mansfield Park on Dido. In the movie, Gadon makes as diligent a husband hunter as any Bennett sister with her Austen-ian schemes to land a man.

Two standouts are Tom Felton and Miranda Richardson (better known to Harry Potter fans as Draco Malfoy and Rita Skeeter), effectively typecast as Lady Ashford and son, a pair of racist gold diggers so singularly malicious they cannot be excused by the ignorance of the times.

Actors we love to hate, Miranda Richardson and Tom Felton are skin-crawlingly brilliant. Boo, hiss, boo, hiss!

Wilkinson is the other standout as Dido’s sympathetic great-uncle/adoptive father William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, a Lord Chief Justice who presided over two landmark antislavery decisions in English Law.

Tom Wilkinson dishes out some good old English common sense as Dido’s firm but kindly guardian, who commissions the portrait.

The major Crisis that awakens Dido’s hunger for identity and truth is Lord Murray’s embroilment in the Zong affair, which she discovers by way of a tense flirtation with a young idealist of low rank, played by heartthrob to watch out for Sam Reid.

Mbatha-Raw shares an impassioned moment with dashing up-and-comer Sam Reid as John Davinier, Dido’s principal love interest.

The crew of the slave ship Zong forced 142 people into the sea alive (including 10 who committed suicide in defiance), then attempted to collect insurance on the murdered slaves. The court case serves as Dido’s first serious encounter with her very precarious privilege in a system that is built on the backs of enslaved people, her own mother among them. The massacre later served as inspiration to artist J. M. W. Turner.

The Slave Ship, or Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon coming on, by J. M. W Turner. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Turner painted this after reading about the Zong Massacre.

Her other major identity crisis comes from learning to love herself amidst the general douchebaggery she endures from people like the Ashfords. Being a source of simultaneous erotic fascination and repulsion in the male gaze really wears down a girl’s self-esteem. Tom Felton’s character puts it bluntly when he states, “One does not make a wife of the rare and exotic…one samples it on the cotton fields of the Indies.” Real-life diarist Thomas Hutchinson was less lewd but equally dismissive and other-ing of her unique brand of beauty, writing, “Her wool was much frizzled in her neck…She is neither handsome nor genteel.”

This crisis comes to a head when Lord Murray commissions the portrait of her with Elizabeth. Fittingly for a movie inspired by a painting, art plays a dynamic rather than decorative role. The representation of black subjects in art of the time is crucial to developing plot and character, particularly as it pertains to Dido’s sense of self worth. In two critical scenes, Dido wanders the halls of Kenwood observing paintings like these:

Portrait of Louise de Kerouaille, Pierre Mignard. National Portrait Gallery, London.

In this portrait of Louise de Kerouaille, mistress of King Charles II, an enslaved black child in elegant dress presents Louise with exotic sea treasures. In the 17th century, such children were marketed as luxury goods for rich women.

Portrait of Helene Lambert de Thorigny, by Nicolas de Largilliere with Jean-Baptiste Belin. Honolulu Museum of Art.

Here, the wife of a wealthy bourgeoisie decorates a floral wreath held up by an African page in a slave collar and turban ensemble. The Honolulu Museum of Art claims that the white woman invites us “into the scene to enjoy the moment’s enchantment.” We think the enchantment may be lost on the boy, whose arms are probably getting tired.

Portrait of a Woman, Possibly Madame Claude Lambert de Thorigny (Marie Marguerite Bontemps), by Nicolas de Largilliere. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Artist Nicolas Largilliere was fond of this motif. He used it several times. Here we see a slave boy in the shadows holding a lap dog. If you look closely, you can see which one is wearing the collar.

Elizabeth Murray, Lady Tollemache, later Countess of Dysart and Duchess of Lauderdale with a Black Servant, by Sir Peter Lely. Ham House, Surrey, UK.

The notorious Duchess of Maitland, Elizabeth Murray (Who coincidentally shares the name of Dido’s portrait partner Lady Elizabeth Murray), poses with a black slave with pearl earring. The Duchess was called “a daughter of Satan” by her own biographer for her wonton sexual, political, and financial exploits. If the nameless black object in this painting is to be believed, she dabbled in human trafficking.

These enslaved pages and handmaidens (usually children) were traded as fashion accessories, like human pets. They were amusing playthings, a nice compliment to one’s outfit and fair complexion, painting props to denote the white sitter’s status. An expensive piece of furniture, a thoroughbred dog or horse…why not throw a child slave in the mix to show people how rich you are. In the eyes of 17th/18th-century imperialists, slaves were no different from Paris Hilton’s purse dogs (though with fewer rights).

When these living dolls outgrew their cuteness, they were typically deported to Caribbean sugar plantations, where most died before reaching adulthood. They went from wearing satin gowns and being hand-fed cream puffs to being beaten and tortured in the cane fields. Back in Europe, their former mistresses wept over sentimental melodramas, and sweetened their coffee with sugar grown in the blood of children they had once pretended to adore.

That human children were trafficked as fashion items is horrifying enough. That wives and mothers could watch children grow up in their households, then discard them like last season’s frocks makes one almost happy that cockroaches will inherit the earth when we finally launch the nukes.

“Good! Good!”

Across the pond on American plantations, slave children served as playmates for the masters’ children, who grew up in isolation miles from other white children. Many people (including art historians) once believed Dido played a similar role at Kenwood, as a personal servant/companion to Lady Elizabeth.

Darnall III, Henry, by Justus Engelhardt Kuhn. Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore (copy).

Here, young Henry Darnall III and his black companion return home from a day of hunting. Interestingly, this is the earliest known painting of an enslaved African in America. Children such as these grew up together, romping in the garden hand in hand, in rare cases educated together and sometimes forming almost brotherly or sisterly bonds. Before you break into a chorus of We are the World, one of these children might be murdered if he tries to leave the plantation. We’ll give you three guesses which one (hint, it’s the one with a silver bondage collar around his neck).

With images such as these in mind, it is no wonder that Dido is mortified when Lord Murray tells her she is to be painted beside Elizabeth. Her only experience with depictions of people of color in art has been as objects of humiliation. That her uncle/father figure would want to have her painted beside a white subject is not just a disappointment…it’s a betrayal.

Dido storms out of his study after protesting the commission and looks at two paintings, one of her biological father with a black attendant, and this painting by Joshua Reynolds:

Lady Elizabeth Keppel, by Joshua Reynolds. Trustees of the Bedford Estates, Woburn Abbey, UK.

Her anxiety is clear; that this is how she will be remembered by future generations of white Murrays; that this, after all, is what her “family” thinks of her. In the devastating scene that follows, she runs to her room, stares at herself in the mirror and tries to claw the blackness off.

Dido claws, rubs and beats her skin after she learns she’s to be painted. Paintings have taught her that black bodies are not beautiful.

Art is crucial to her understanding of her own identity. Her coloring is treated as abject in paintings, so she sees herself as such. She does not look like a “pure English rose,” the only standard of beauty she has to compare with her own.

Later, she pauses under a tavern sign depicting a black slave kneeling before his white master. She remarks, “Just as in life…we are no better in paintings.”

Dido’s first great triumph of self-realization occurs when the finished portrait is unveiled. She sees that she has been depicted with beauty and dignity, beside Elizabeth as a sister, not a slave. Entreating her father to rule in favor of human rights in the Zong case, she says, “You break every rule when it matters enough Papa, I am the evidence…this painting is the evidence.”

The Movie version of the portrait with Mbatha-Raw and Gadon’s faces, adapted to modern tastes.

The movie updates the painting to suit modern tastes. Dido is racially neutralized with her hair loose in the Western fashion. She and Elizabeth appear to be equals in every way. The movie version is more politically correct (dare we say whitewashed?)

The original Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray, traditionally attributed to Johann Zoffany at Scone Palace in Scotland.

In the original painting, Dido and Elizabeth are near equals. Dido’s otherness is denoted by an Orientalist turban and bowl of exotic fruit. Her sensuous mode of dress and coquettish gesture compared to Elizabeth’s rigid pose suggest a Romantic idea of “Africanness.”

In contemporary terms, the movie version of what it meant to be a black woman of status was a bit more like this…

whereas the original painting was a just a tad more like this…

But the original artist gets an A for effort. It was radical for the time and the first of its kind: a black and white sitter at equal eye level with a direct gaze at the viewer. Their pose is affectionate, and it appears the artist had a great deal of interest in Dido, and shared a strong rapport with her…perhaps even stronger than his rapport with the somewhat stiff Elizabeth.

Like the painting that inspired it, Gugu Mbatha-Raw’s performance is a charismatic and honest portrait. She takes us on Dido’s odyssey to find herself which happens through the traumatic, but ultimately healing power of art.

By: Griff Stecyk