More about Atsuko Tanaka

- All

- Info

- Shop

Works by Atsuko Tanaka

Contributor

In 1994, the critic Aomi Okabe realized that she had to make a documentary about artist Tanaka Atsuko, which she would release four years later under the title Tanaka Atsuko: Mōhitotsu no Gutai (Another Gutai).

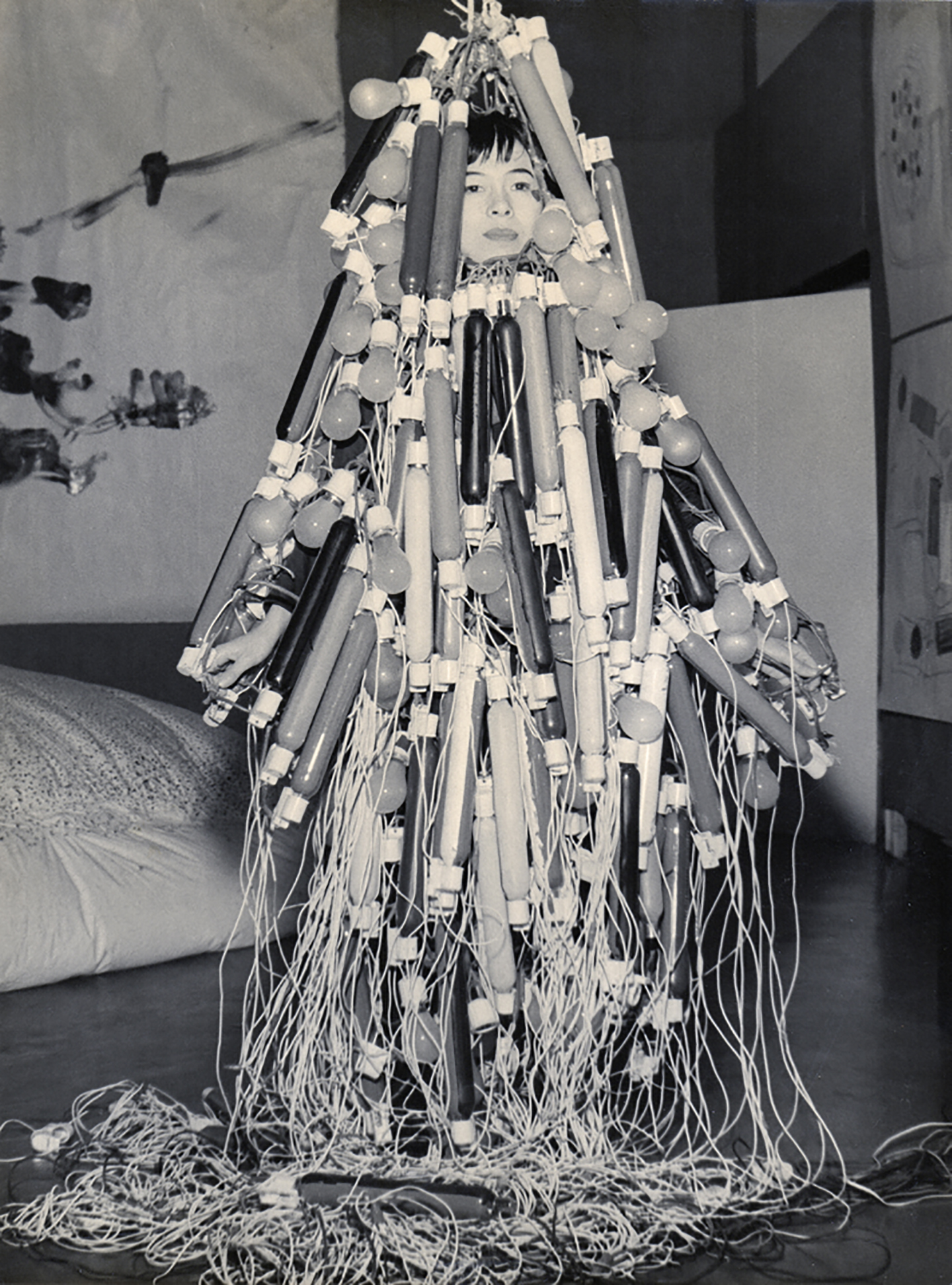

In 1985, when Okabe first visited Tanaka's studio, in Asuka, Nara, Japan, she brought some people she knew from the Georges Pompidou Center in Paris. Since the mid-50's, people in Europe and the U.S. had been hip to Tanaka's singular art practice, but, aside from her very famous and public appearance wearing a dress made of about one hundred painted tubes and eighty functioning light bulbs, complete with circuitry, she was a bit of a J.D. Salinger type. This was compounded by the fact that Asuka, near Osaka, was at the time to Japan almost what Montana is to the U.S.— off the beaten path, rural, not the place where people would predict that an art movement would start.

The archipelago of Japan is presided over by the longest-running imperial dynasty in the world, which has been producing emperors even longer than "The Simpsons" has been on Fox. The Japanese had some contact with other continents over the years, even making an African man, and a European man, members of the samurai order, but they didn't officially open their doors until 1867. When Tanaka was about twenty, and the country had been open to foreigners for only about eighty-five years, she met her future husband, Akira Kanayama, who was an art student working in the abstract expressionist idiom.

After WWII, the U.S. occupied Japan for seven years, and it was at the end of this occupation that Kazuo Shirahaga, Saburo Murakami, Kanayama, and, later, Tanaka, with about twelve others, formed the 0 society of artists. In a show of true DIY practicality, the 0 society held an exhibition in the window of the Osaka Sogo department store. During this period, Tanaka was very ill, and, like many artists, she used this obstacle to develop her practice. During a prolonged period of hospitalization, she started writing numbers, signifying her remaining days of confinement, on cloth, cutting up the cloth and reassembling the pieces, which became her Calendar work. When she got out of the hospital, both she and Kanayama became associated with Jiro Yoshihara's Kansai-based Gutai movement, whose artists used unusual strategies to make their works, such as running through pieces of paper, wrestling with mud, and dropping glass jars of paint on canvases. Tanaka was, by most accounts, the only woman in the Gutai movement, and some critics say that she was never really in the movement at all. The way I understand it is that she joined in the way that someone in the U.S. might join the 4-H Club in a rural area or the Residence Hall Association in a college: it's a way to network, it can bring opportunities, and, as Lou Reed would say, it's something to do.

At that time, it seems that all the cool kids in Tokyo and Paris were convinced that art must submit itself to the revolutionary passions of building a Marxist/Leninist dictatorship of the proletariat, rather than exploring sensation, form, color, and other enjoyable things, so the 0 society and Gutai were distinctly unfashionable, as they neglected to explicitly dedicate their practice to the loyal service of the revolution. Not until 2012 did Tanaka finally get a large retrospective exhibition in Tokyo, and her first solo exhibition in North America was in 2004. Sexism might also be at play here, though. Goro Nagasaka, Tanaka's long-serving psychologist, told Aomi Okabe that sexism took a considerable toll on Tanaka's mental health.

At the same time, Tanaka and Kanayama, like a team, didn't go for the traditionalist strain of art which conspicuously magnified traditions of Zen art, like Jiro Yoshihara's series of perfect circle paintings. Because of this, Okabe writes, the works of Tanaka and Kanayama barely appear Japanese, as they consist of "concrete" everyday objects and physical engagement, which is very accessible to foreigners. Such decisions are evidence of Tanaka's enormously successful ambition of building a universal language that goes beyond nationalism, regionalism, and even the division of artworks into different formal categories. For instance,Work (Bell), which prompts you to interact à la Felix Gonzalez-Torres, sets off a chain of twenty loud bells, at two-meter intervals on the floor, which ring in succession across a gallery. "Please push the button," says the unassuming placard next to an old-fashioned doorbell. When he obeyed the direction, Holland Cotter recalls, "visitors absorbed in the artist's paintings flinched and glared. I shrugged apologetically." For Tanaka, Work (Bell) is actually a painting, which made perfect sense to her but was harder than quantum mechanics for most critics to understand. How could a painting be made of bells?

In Japan, the term "concrete," the most common English translation of "Gutai," also means particularity and specificity. Takana's use of the Gutai mode of art-making had a significant influence on "happenings" and performance art in other parts of the world. In this sense, you could say that Tanaka is the first woman to attain recognition as a conceptual artist. Before she put on her Electric Dress, for instance, she performed Stage Clothes in front of an audience, which involved her removing layers of clothing connected seamlessly to other garments, so that as each garment comes off, another one appears in its place. The Byzantine circuits and plugs both made the mechanics of the dress possible and developed as a theme throughout all of her work. Her diagrams of the dress are like her later paintings, whose titles epitomize her signature reticence and fascination with rationality, numbers, sequence, connections, and mechanisms.

Sources

- "具体美術協会〈GUTAI〉の買取評価や人気作家について." baku-art, Mar. 31, 2020, https://www.baku-art.co.jp/smartphone/businessblog/otaku/2020033137.html.

- おかべあおみ, "監督制作記 岡部あおみ." Ufer! Oct. 1998, https://www.ufer.co.jp/works/tanaka/record01.html.

- "田中 敦子." Kosho, https://www.kosho.or.jp/products/search_list.php?search_word=%E7%94%B0%….

- Cotter, Holland. "With Bells and Flashes, Work of a Japanese Pioneer." The New York Times, Oct. 1, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/01/arts/design/with-bells-and-flashes-w….

- 森大志郎, "0会." artscape, Jan. 15, 2009, https://artscape.jp/dictionary/modern/1198154_1637.html.

- 伊東正伸, "田中敦子―アート・オブ・コネクティング―." ART iT, Mar. 8, 2012, https://www.art-it.asia/u/admin_ed_exrev/xkcyq6o0xillygdtgez9.

- 加藤瑞穂、池上裕子, "白髪一雄オーラル・ヒストリー." Oral History Archives of Japanese Art, Aug. 23, 2007, http://www.oralarthistory.org/archives/shiraga_kazuo/interview_01.php.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Atsuko Tanaka (artist)

Atsuko Tanaka (田中 敦子, Tanaka Atsuko; February 10, 1932 – December 3, 2005) was a Japanese avant-garde artist. She was a central figure of the Gutai Art Association from 1955 to 1965. Her works have found increased curatorial and scholarly attention across the globe since the early 2000s, when she received her first museum retrospective in Ashiya, Japan, which was followed by the first retrospective abroad, in New York and Vancouver. Her work was featured in multiple exhibitions on Gutai art in Europe and North America.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Atsuko Tanaka (artist)